Ten books, six operas, two months in prison, and multiple sheepdogs named Pan: The remarkable life of Woking's Ethel Smyth

Surrey resident Dame Ethel Smyth was one of history's truly extraordinary characters. She was a great composer, a prolific writer, a suffragette, and a sportswoman, as well as having multiple romantic relationships with other women.

Surrey resident Dame Ethel Smyth was one of history's truly extraordinary characters. Her musical career, as one of the greatest British composers of the 19th and and 20th centuries, and the first woman to be given a damehood for her work as a composer and a conductor, is enough to win her a place in the history books alone.

But her remarkable musical career was also combined with being a prolific writer and author, publishing ten books, serving as a radiographer in the First World War, being imprisoned for her activities as a suffragette, mountain-climbing, tennis, golf, having multiple sheepdogs named Pan, wearing masculine clothes, and romances with many women (and one man), including falling in love with author Virginia Woolf at the age of 71!

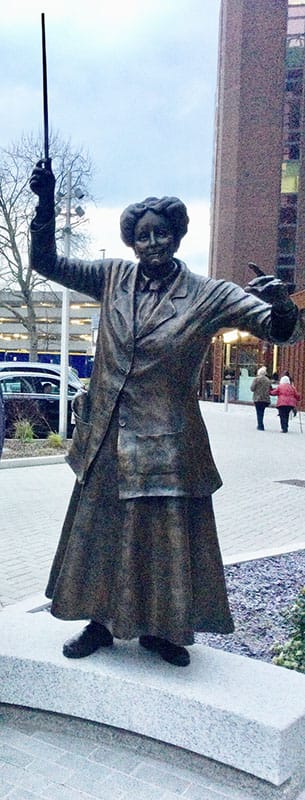

Ethel's storied life took her across the world, but she lived most of in Surrey, including the last 34 years of her life which she lived in Woking (in a house chosen for its proximity to the golf course), where a statue of her was unveiled in 2022 on International Women's Day.

Often she is remembered as a leading suffragette, yet her campaigning for women's right to vote was just one chapter in an incredible and full life. Doing it justice would take an entire essay, so that is exactly what we've written. So grab a coffee, and settle in.

We hope you like this article. It couldn't exist without the generosity of our subscribers. If you'd like to support our work, and if you can afford it, please consider using the button below to support high quality journalism for just £5 a month.

Woking Golf Club, 1937

Imagine you are sitting on the veranda at Woking Golf Club in the autumn of 1937, looking across the green. In the distance you might spot an elderly woman dressed in men's tweed clothes, a wonky hat upon her head, accompanied by a shaggy Old English sheepdog, painstakingly searching through the rough in search of a lost golf ball.

You recognise her of course. This is Dame Ethel Smyth, famous composer and suffragette, and stalwart of the Ladies section of the golf club.

You've heard her music played on the BBC, in fact it feels like you've heard that bit from her opera about Cornish pirates every single time you've listened to the Proms (because you have). You know she was imprisoned with Mrs Pankhurst and you remember hearing that her latest autobiography was popularly received. You know she shares her birthday with William Shakespeare and that she's completely deaf. You remember the furore when she flouted the club rules by marching through the Men's section of the club, and you also remember that no one dared to say a word to her about it.

Most of all, you know of her proud boast that she has never, ever lost a golf ball. And, as you watch her diligently poking through a bush with a golf club, you're certain she's not about to start now.

'I am the most interesting person I know and I don't care if no one else thinks so!'

Ethel Mary Smyth was born in 1858, in what is now Greater London, the fourth child of eight children. Although she was born on 22 April, Smyth's family always celebrated her birthday the day after on 23 April, because that was William Shakespeare's birthday, and throughout her life that was the date she habitually stated as her birthday.

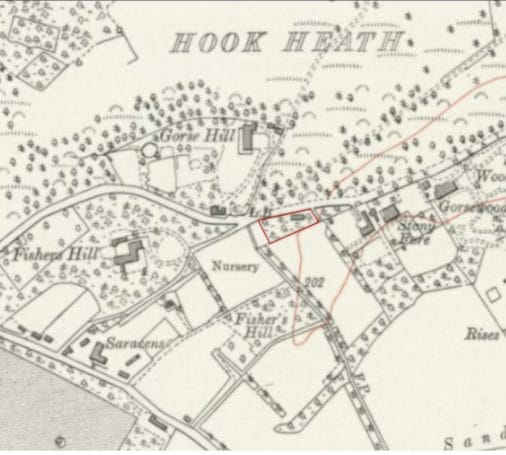

Her father was John Hall Smyth, a major general in the Royal Artillery, and in 1867 he moved his family to Frimley Green after he became stationed at the Aldershot garrison as commander of his regiment. Later the family moved to Hook Heath on the outskirts of Woking, starting Ethel's lifelong connection with the town.

Ethel was a child prodigy, playing the piano from a very young age and composing her first hymn at age 10, partially as the result of her German nanny, who had been trained as a pianist in Leipzig. By age 12 Ethel was determined to study music and to become a composer, and by age 17 she was studying with Scottish composer Alexander Ewing, who, like her father, was also a career army officer and stationed at Aldershot.

Ewing introduced Ethel to Wagner's operas and recognised as a "born musician who must begin her formal training at once" but her father vehemently disapproved of her intention to pursue a musical career and initially forbade it.

Her father's opposition had been understandable. At the time women were completely shut out of composing because no one would play their music or hire them to direct an orchestra. Just a generation earlier Emilie Mayer had been hailed as a 'female Beethoven' but had been forced to hire her own orchestras and venues simply to be able to get her music played, and had been forced to retire when she ran out of money. Additionally, for an upper middle-class woman, any kind of independent career would be a permanent barrier to marriage and motherhood.

However, Ethel was determined both never to marry and to have a career as a composer despite how impossible it seemed. To give a sense of her self-confidence at this time, an acquaintance from this time recalled 15-year old Ethel once declaring "I am the most interesting person I know and I don't care if no one else thinks so!"

Needless to say, she got her own way in the end, in part due to the support of her mother. Eventually her father relented and at age 19 she was permitted to leave, unchaperoned, for Germany to continue her musical education at the Leipzig Conservatory.

Leipzig

Ethel arrived in Leipzig in 1877, and stayed there for the next 13 years studying and writing music, returning to Surrey every summer. During these years she met and developed connections and friendships with many important composers, including Tchaikovsky and Brahms, the latter of whom she detested for his sexist behaviour, and she also fell in love more than once. Indeed, before she had even been there a year Ethel had fallen in love with the actress Marie Geistinger, even writing the Geistinger Sonata in her honour, and starting a lifelong habit of writing music for the people she loved.

However, Ethel was also disappointed with the stilted quality of teaching at the conservatory, and left after a year to continue her studies privately with Austrian composer Heinrich von Herzongenberg who took her on as his sole pupil. His wife, Elisabeth von Stockhausen (also known as Lisl), was a musical genius in her own right, and the couple, who had been unable to have children, came to treat Ethel as a surrogate daughter.

Ethel and Lisl, who were only 11 years apart in age, became incredibly close with each other, and it was through Lisl that Ethel met Henry ("Harry") Brewster who became probably the greatest love of her life but who was unfortunately already married to Lisl's sister, Julia.

Although Julia and Harry Brewster had two young children, they had previously agreed to what would now be termed an 'open marriage' with an agreement that they would separate if either of them ever fell in love with anyone else. Harry fell in love with Ethel when she stayed with Julia in Venice during the winter of 1882, causing him to leave abruptly for Africa to try to get over his infatuation, though Ethel later wrote "for my part, wholly taken up, as usual, by the woman, I had not the faintest [idea]".

However, Ethel visited the Brewsters again, at Julia's invitation, in the winter of 1883, staying until summer 1884, and during this visit fell in love with Harry in return. Julia had apparently anticipated this, and at first insisted that she merely wanted to be sure that her husband and Ethel were truly in love before she gave their relationship her blessing, but in fact had been hoping that Ethel would decide to break off the relationship with Harry.

The love triangle came to an end in 1885 when Julia met with Lisl to discuss the matter and it became clear to Lisl that Julia could not bear to lose her husband. Although Lisl did not personally blame Ethel, Lisl's mother was insisting that Lisl choose between 'that wicked English girl' and her family, and Lisl was forced to cut ties with her surrogate daughter, at the same time that Ethel cut ties with Harry for Julia's sake.

This turned out to not be the end for Ethel and Harry, but Ethel returned to England miserable, and remained estranged from her beloved Lisl who she never saw again before Lisl's sudden death in 1892.

Musical success

Despite her heartbreak, Ethel's musical career continued unabated and in 1890 she debuted in England, at age 32, with a composition called Serenade in D at the Crystal Palace, and just three years later her music was being performed in the Royal Albert Hall, gaining her recognition as a serious composer; although she would also spend much of her career being dismissed and marginalised as a 'woman composer'.

In addition to numerous songs and orchestral pieces, Ethel also wrote six operas, the third of which was The Wreckers (1906) and is possibly her best known work, telling a tale of fanatically religious Cornish villagers luring shops onto rocks in order to plunder the wrecks. The Wreckers has been described as the most important English opera of the period, and had been inspired by a trip to Cornwall the year after Ethel's return from Leipzig where she later wrote that she had been "haunted by impressions of that strange world of more than a hundred years ago; the plundering of ships lured on to the rocks".

Ethel spent years visiting places where wrecking had been committed, making notes and interviewing anyone with memories of them, and finally passed the notes to Harry Brewster (yes, him!) who wrote the script, or 'libretto', for the opera to accompany her music. The opera was originally written in French (Hary's preferred language) as 'Les naugrageurs', partly on the basis that Ethel thought there was a greater chance of getting the opera performed on the continent.

However, after five years of "striding about Europe, cigar in mouth" trying to sell her opera, Ethel ended up returning to Leipzig in 1906 to secure her first performance of The Wreckers, in a German translation. But, while the opera was highly acclaimed on opening night Ethel was incensed by what she considered a poor translation and by major cuts imposed by the conductor; when he refused to restore the cut material, Ethel marched into the orchestra pit to confiscate the music sheets, preventing any further performances.

An attempt to perform the opera in Prague also failed, due to under-rehearsed performances, and Ethel returned to England where, with the support of Thomas Beecham (a friend and concert organiser who would later found the London Philharmonic), the opera was performed by his new orchestra for the first time in English. The opera proved such a success that its overture was played at the Proms 27 times between 1913 and 1947.

Another successful opera of hers was the German-language Der Wald (The Forest) which had preceded The Wreckers and was the first opera by a woman composer ever performed at New York Metropolitan Opera ('the Met') in 1903. Despite being popular, and a financial success, it remained the only opera written by a woman performed at the Met until 2016, over a century later.

Ethel's musical career would continue successfully into the 1920s, being made a Dame for her services to music by King George V in 1922. However, this was also around the same time it was being prematurely cut short by hearing loss, and her career might have been even more successful had it not been for the disruption caused to it by her work with the suffragettes and in the First World War.

"Life, strife — these two are one, naught can ye win but by faith and daring."

In 1910 a 52-year-old Ethel started to associate with the women's suffrage movement for the first time. She was a close friend of the trio of sisters, led by Millicent Fawcett, who lived together and were all members of the NUWSS (National Union of Women's Suffrage Societies), and Ethel even lived with them for a time in West Sussex, which presumably marked her introduction to the movement.

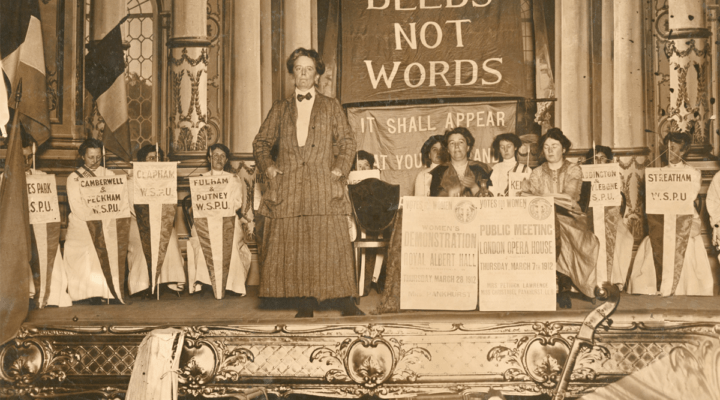

In September that same year, most likely through the sisters, Ethel first met Emmeline Pankhurst, the leader of the WSPU (Women's Social and Political Union), an organisation which would change the course of her life.

Ethel was captivated by Pankhurst's politics, but also enchanted with the woman herself — in fact, she was so besotted with Pankhurst that she temporarily left for Egypt to temper her infatuation, and later dedicated a memoir, Female Pipings in Eden, to her in 1934.

Although by her own admission Ethel had not been interested in politics previously, her commitment to the suffragettes was clearly sincere and strong. She became a dedicated activist, going so far as to pledge two years of her life to the cause. In 1911, for instance, she refused to fill in her census form (writing "No Vote, No Census" across it as a protest), organised for Pankhurst to speak at a meeting of Woking suffragettes, and even composed The March of Women, which became the anthem of the movement:

By 1912 the WSPU, which represented the more radical wing of the movement, was frustrated with failures by parliament to pass bills giving women the right to vote and with the aggressive police reponse to their protests in London. With a third bill on its way to yet another narrow defeat in March that year, Pankhurst called off the truce which had seen the suffragettes refrain from their campaign of violent protest.

The WSPU planned to mark the end of the truce with two provocative nights of window smashing in central London, targeting the homes of prominent politicians especially. Pankhurst was to lead the action by smashing the window of No 10 Downing Street as part of a coordinated operation where pairs of women, armed with hammers, would all attack windows at 5.30pm to overwhelm the inevitable police response.

However, Pankhurst had never played ball games and had no practice at throwing stones. Ethel therefore brought her to her family's home on the outskirts of Woking where, at dusk, Ethel had Pankhurst practice by throwing stones at a tree in the garden.

It did not go well. By Ethel's own account: "The first stone flew backwards out of her hand, narrowly missing my dog. Once more we began at about a distance of about three yards, the face of the pupil assuming with each failure – and there were a good many – a more and more ferocious expression."

Unfortunately, despite the practice, Pankhurst was unsuccessful at her attempt at breaking the window of No 10, with her stone landing harmlessly nearby, but another suffragette, accompanying her as a contingency, did manage to smash the window before they were both arrested.

Ethel, however, was far more successful with her target. In a recorded interview with Vera Brittain in 1937, she spoke proudly about she managed to break the window of the Colonial Secretary in Berkeley Square, as revenge for a remark he had made about how women could have the vote when they were all as "pretty and wise" as his wife. She was arrested immediately and offered no resistance other than to confirm with the constable that she had indeed successfully broken the window!

Over 260 women were arrested across the two days of protest, overwhelming the prison system as the WSPU had intended.

Many of them, including Ethel herself, were bailed out of the police station by another Surrey hero of the suffragette movement, Frederick Pethick Lawrence. Pethick Lawrence, who lived in Dorking with his wife (the WSPU's treasurer), was a staunch supporter of the movement and used his immense family wealth to bail out over a thousand suffragettes before he was bankrupted by government campaign to target the WSPU's financial supporters.

In Ethel's own words:

I broke my window successfully and was bailed out of Vine Street at midnight by wonderful Mr Pethick-Lawrence, who was ever ready to take root in any police station, his money bag between his feet, at any hour of the day or night.

However, Ethel was then prosecuted and sentenced to three months in Holloway Prison, as part of a government clampdown in which hundreds of suffragettes were given stiff sentences for actions which previously would have earned a sentence of just a few days.

Due to overcrowding, Ethel was released after just three weeks, but during her time in prison was famously observed (by Thomas Beecham) using a toothbrush to conduct other inmates, through the bars of her cell, in a rendition of The March of Women as they marched round the exercise yard.

Although Ethel doesn't appear to have participated in the suffragette prison hunger strikes, or been subjected to forcefeeding, the same could not be said for Pankhurst, who was wasting away during this period due to repeated hunger strikes, and stayed with Ethel to recuperate in Woking in 1913.

It was most likely this stay which inspired Ethel to write a song, Possession (1913), which is dedicated to Pankhurst and was written while she was watching Pankhurst waste away. Dr Leah Broad, a historian specialising in women in music, has described Possession as:

A song about letting go of somebody who you love because you know you can’t control them and hold onto them. It’s so poignant, and it just encapsulates their relationship at that particular point so well and it’s a beautiful piece of music.

The end of 1913 marked the end of Ethel's two-year pledge to the suffragettes, and she stepped back from political activism to return to her musical career. Because she found herself unable to resist activism while in England, she began with a visit to Alexandria in December that year, where she began work on her fourth opera, The Boatswain's Mate.

By May 1914 she was in Vienna to arrange the production of two of her operas, and by 1 July she had succeeded in arranging several performances of her work in Germany and had travelled to France to meet up with Pankhurst where she was recuperating following release from prison.

However, that same month was also the 'July Crisis', where European leaders were frantically trying to avoid the outbreak of a major European war. By 28 July Austria was shelling Belgrade and, as Ethel wrote, "by midnight on August 4th all Europe was at war."

War Work

The outbreak of war was, aside from its far greater human tragedies, a disaster for Ethel's career as all her productions across Europe were, unsurprisingly, cancelled, right at the very point when she had been being acclaimed as an equal to Tchaikovsky.

Ethel, however, seems to have taken the war largely in her stride, despite the huge blow it was to her music, and swiftly returned to England with Pankhurst.

As the daughter of a military family, Ethel was determined to help the war effort, and by 1915 she was in Italy, joining her sister Nina who had partnered with the painter Lady Helena Gleichen to raise an ambulance outfit which would later be decorated for valour.

Later that same year Ethel, aged 57, returned to Paris to train as a radiographer, and joined the XIIIth Division of the French Army at the huge military hospital in Vichy where she worked as a volunteer, helping to locate shrapnel fragments inside wounded soldiers.

Since the wartime composition made composing impossible, Ethel turned to writing instead, penning her first memoir, Impressions That Remained, as a distraction from the horror around it. In a later book she would give a typically to-the-point description of the experience:

Locating bits of shell, telling the doctor exactly how deeply embedded they are, watching him plunge into a live although anaesthetised body that shall prove you either an expert or a bungler is not a music inspiring job, but writing memoires in between whiles was a delightful relief.

By January 1918 women in Britain were finally given the right to vote, to Ethel's immense satisfaction, and in March she managed to return to England, with great difficulty due to the German Spring Offensive, and later travelled to Italy for the war's end where she worked as an interpreter for the Red Cross.

After the war Ethel returned to the promotion of her music, assisted by several enthusiastic supporters and patrons, and the next decade marked a time of professional success. By 1928 her music had become a regular at The Proms and the BBC marked her 60th birthday with a 'musical jubilee' in which they broadcast two of her concerts to the nation.

'Let there be banners and music!'

Ethel would today most likely be described as a 'lesbian', although her romantic life was much more nuanced than this label might suggest.

For her own part, Ethel never labelled herself one way or the other, but was clearly aware of homosexuality, as she once discussed 'Sapphism' with Empress Eugenie, the widow of Napoleon III, in Farnborough. (The Empress, for her own part remarked, "if you gave me a wife I swear I wouldn't know what to do with her!")

But despite never labelling herself, Ethel made no secret of her relationships with women throughout her life, and wrote openly about her attraction and love for them in her memoirs, including that she had always found it "easier to love my own sex passionately, rather than [men]".

However, Ethel also often developed unrequitted feelings for other women, and it can therefore be difficult to disentangle her romantic relationships from her close friendships with a dizzying array of important women, which included such figures as Empress Eugenie, Pauline Trevelyan, Lady Mary Ponsonby and Princess Edmond de Polignac, several of whom were important patrons of her work as well as friends.

For instance, at the age of 71 Ethel met the author Virginia Woolf, who wrote of the experience that "An old woman of seventy-one has fallen in love with me....It is at once hideous and horrid and melancholy-sad. It is like being caught by a giant crab."

Yet Woolf, as was the case with many of Ethel's romantic interests, also became a close friend and admirer of hers, exchanging letters about literature and writing to her two years later:

Look dearest Ethel…. Please live 50 years at least; for now I’ve formed this limpet childish attachment it can’t but be part of my simple anatomy for ever — wanting Ethel — I say, live, live, and let me fasten myself upon you, and fill my veins with charity and champagne.

Virginia Woolf herself would suggest that Ethel and Emmeline Pankhurst had been lovers, writing "in strict confidence" that they had once shared a bed, but it is still debated whether or not this actually happened, as some believe it is unlikely that Pankhurst would have risked a scandal, and it may well be that Ethel never actually never had a physical relationship with any woman.

Nevertheless, Lady Mary Ponsonby was probably Ethel's longest lasting romance.

Ponsonby was a political radical from an aristocratic family, whose own life is fascinating in its own right and included such highlights as: being a maid of honour to Queen Victoria, helping to found the first women's college in Cambridge, corresponding with Thomas Huxley about evolutionary biology, and arguing with H. G. Wells about socialism.

Ponsonby's husband had died in 1895, when she was 63 and, newly single, she began a very happy triangular romance and friendship with both Ethel Smyth and Violet Paget (a popular author of the period). Ethel spent ten years with Ponsonby, a period she described as "the happiest, the most satisfying and for that reason, the most restful of all my many friendships with women", and they would correspond for a further 15 years until Ponsonby's death in 1916.

Ethel had the misfortune to outlive most of the people she loved, and this was also true of the only man she ever had a relationship with, Harry Brewster, who was also the most important love of her life.

Their romance had resumed by chance in 1890, when Harry had happened to be in London at the time of Ethel's musical debut at the Crystal Palace in 1890 and bought a ticket to see it, where Ethel had spotted him in the audience.

Following a frank conversation over tea about their continuing feelings for each other, they resumed their romance; initially through long-distance letters with the begrudging consent of Harry's wife Julia.

Following Julia's death, Ethel rejected a marriage proposal from Harry on the grounds it would interfere with her work as a composer, but she and Harry continued their romance for the rest of his life, with Ethel probably having sex with him at least once during a trip to Paris; a deliberate decision on her part due to not wanting to remain what she called a 'Stonehenge virgin'.

Harry was a talented writer and he and Ethel both supported each others work. Henry wrote librettos (scripts) for Ethel's operas and Ethel set pieces of his writing to music. After his death in 1908 she even turned his most famous book, The Prisoner, into an opera (The Prison), though it had to wait until 1931 for its first performance.

Before his death Harry had moved to South Farnborough to live with his daughter and son-in-law, just three miles away from Ethel. During his final sickness Ethel visited him daily, and was holding his hand when he died, just as she had done with her father fourteen years earlier.

Ethel mourned Harry for the rest of her life, writing movingly about him to Emmeline Pankhurst in May 1914:

And then two great yearnings came...for Pan [her first sheepdog] and for Harry.

I have had one of my fits – they generally come with rather relaxed mental states...of longing for Harry...just his smile and the way he used to say “Ethel!” when we met after a long parting;-a longing that presses slow tears out of my eyes.

Is it possible to believe that two beings so woven into each other can ever lose each other? I cannot believe it; it cannot be.

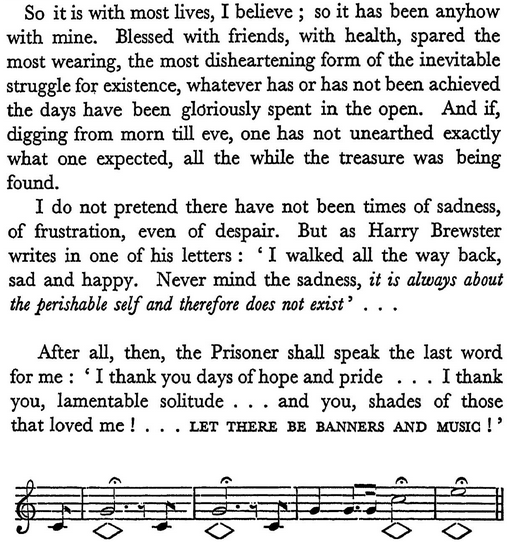

That Harry Brewster and Lady Mary Ponsonby were Ethel's greatest loves is clear from the fact that they featured heavily in Ethel's final published autobiography, in which she published a selection of her correspondence with both of them. However it was Harry to whom she deliberately gave the last word, finishing the book with a quote from The Prisoner, where the protagonist declares defiantly:

"LET THERE BE BANNERS AND MUSIC!"

Later Years in Woking

Ethel travelled extensively in her life, but always came back to Woking. She lived at the Smyth family home in Frimley Green for many years, before moving to a cottage nearby which she rented until 1909 until, with her landlady intending to raise the rent, she was forced to move out.

However, the year previously she had met a wealthy patron, Mary Dodge, who had been so impressed by a performance of The Wreckers that she offered Ethel £1,000 on the spot to pay for a week of performances in the West End.

Ethel happened to mention her need to move during a stay with Dodge at Ashdown Forest, and Dodge immediately insisted that Ethel ought to have a house of her own, which Dodge would buy for her.

Ethel was a keen sportswoman (in addition to being a passionate golfer she was also a mountain climber, a cricketer and a tennis player), so Dodge insisted that Ethel buy herself a home both within commuting distance of London and also near a good golf course. One of Ethel's old cricket friends was placed in charge of the search, and eventually found a plot of land at Hook Heath, right next to Woking Golf Club (of which Ethel had been a lifelong member), where a cottage was built for her at Dodge's expense.

Ethel would live in this cottage for the last 34 years of her life, during which time she would turn to a successful writing career after her hearing finally failed her, ultimately publishing ten books in all, with another left part-written at the time of her death.

Although she was a talented, and commercially successful writer, the loss of her hearing weighed heavily on her, writing in her final autobiography (As Time Goes On) that:

"Occasionally, but very very rarely, I still got pleasure from listening in, and from records, especially if the music were unknown to me. Then, only a few months ago, what is called distorted hearing set in ! . . . So good-bye music !

'But,' the reader may remark, 'you can still compose, anyhow.' One can, but I confess that to me half the fun of composing has always been hearing what I have written."

In 1937, the year after that autobiography was published, a festival celebrating her music was organised under the direction of her old friend Thomas Beecham, culminating in a sold-out Royal Albert Hall performance, to celebrate Ethel's 75th birthday.

Yet by this point Ethel was completely deaf and was tragically unable to hear either her own music or the applause of the crowd.

However Ethel was not lonely. During these years she had a succession of large Old English sheepdogs named Pan, and continued enthusiastic friendships throughout her life, bringing her hearing aid (and its beer-crate-sized battery) to meetings of Virginia Woolf's Bloomsbury Group. She also continued her lifelong love of sport, spending hours on the golf course where, as Surrey Heritage puts it:

It was her proud boast that she never lost a golf ball and she would spend hours, accompanied by her dog, searching through the rough for the result of a ‘directional error’!

Ethel Smyth died at age 86 in 1944, having contracted pneumonia after a fall in her home.

She was cremated at Woking Crematorium and her ashes were scattered in the woods next to Woking Golf Club by her brother, Robert, in accordance with her requests.

Legacy

Unfortunately no recordings were made of Ethel's music or work as a conductor during her heyday, and this is partly the reason why her work was largely forgotten after her death.

Her legacy also suffered due to her work as a suffragette, with much media coverage during her lifetime choosing to focus on her political reputation at the expense of her music, despite her popularity. The New York Times, for instance, chose 'A Militant Victorian' as its headline for an article reviewing her memoir.

Ethel's work had to wait until the 21st century to be rediscovered, and for there to be a concerted effort to perform and record her music. Several of her operas have been performed in recent years, including The Wreckers which was finally performed in its original French in 2022 by Glyndebourne Opera, and much of her music can now be listened to online thanks to these efforts.

(A 2015 English-language performance of The Wreckers can be viewed in full online thanks to the American Symphony Orchestra).

Interest in Ethel's life and work increased further around the 2018 centenary of women's right to vote, with various plays and performances based on her life and work taking place, and in 1922 a statue of her was unveiled in Woking town centre.

The larger than life statue, cast in bronze, was created by the artist Christine Charlesworth, and depicts Ethel in her role as a conductor:

But regardless of her legacy, Ethel Smyth remains, first and foremost, an extraordinary woman who lived an extraordinary life to its fullest. As she put it in on the last page of her last book:

So it is with most lives, I believe ; so it has been anyhow with mine. Blessed with friends, with health, spared the most wearing, the most disheartening form of the inevitable struggle for existence, whatever has or has not been achieved, the days have been spent gloriously in the open. And if, digging from morn till eve, one has not unearthed exactly what one expected, all the while the treasure was being found.

I do not pretend there have not been times of sadness, of frustration, even of despair. But as Harry Brewster writes in one of his letters : 'I walked all the way back, sad and happy. Never mind the sadness, it is always about the perishable self and therefore does not exist' . . .

After all, then, the Prisoner shall speak the last word for me : 'I thank you days of hope and pride . . . I thank you, lamentable solitude . . . and you, shades of those that loved me! . . . LET THERE BE BANNERS AND MUSIC!'

This article would not have been possible without, and draws upon, the work of Surrey Heritage, The Marginalian, mdw, and the Donne Foundation.

Comments ()